WASHINGTON — In the late 1920s, when the Soviet Union embarked on the task of rapid development of its industry, it quickly realized the money for implementing the large projects envisaged was lacking. Industrialization required a lot of financial resources, and one of the options with which the Soviets tried to fill the gap was the sale of masterpieces from the USSR’s museums, particularly from the main museum of Leningrad (modern day St. Petersburg), known as the Hermitage.

Several Armenians played an interesting role in this enterprise, both in the USSR and outside. Some sources suggest that between 1928 and 1935, the Soviets sold 24 thousand artworks, including 2,800 paintings from the Hermitage. British-American historian Dr. Jonathan Conlin noted that the Armenian billionaire and art collector Calouste Gulbenkian became the first “to go shopping at the Hermitage Museum.”

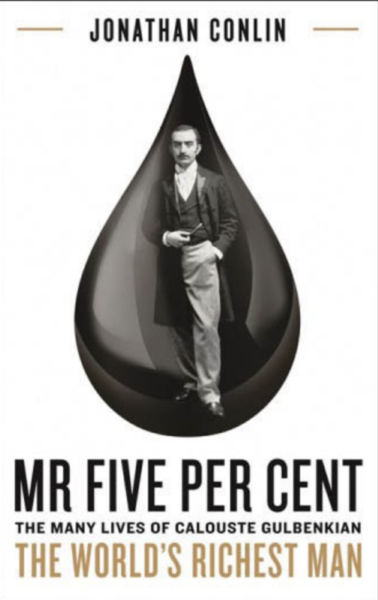

“In total, he paid 17 million dollars in today’s values to the Soviet Union,” noted Dr. Conlin in an e-communication. Gulbenkian’s main competitor, who also purchased artifacts from the USSR, was an American businessman and benefactor, Andrew Mellon, who also served as the US Secretary of Treasury when the transactions were taking place. Dr. Conlin, who authored a monograph about Gulbenkian, tracked differences between the approaches of Gulbenkian and Mellon in selecting artifacts from Russia.

“With Mellon, I very much have the sense that he was basically ticking famous artists off a list that other people have written. In the case of Gulbenkian, he does go after some very well-known artists like Rembrandt, but he also acquires examples of silverware by 18th century French silversmiths as well as some other pieces which by no means were obvious choices,” noted Conlin, adding that the choices he made really do reflect that the Gulbenkian collections were formed by Gulbenkian himself.

Gulbenkian acquired some Armenian artifacts. However, the core of Gulbenkian’s collection represented masterpieces like “Pallas Athena” and “Tutus” by Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (17th century), “Helena Fourment” by Peter Paul Rubens (17th century), Dirk Bouts’ “Annunciation” (15th century), and the sculpture of the Greek goddess “Diana” by French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon (18th-19th centuries).

The Armenian oil magnate had established relations with the Soviets earlier when he helped the new Soviet republic sell Russia’s oil in the international markets. Back then and later, he worked with Georgy Pyatakov, the trade representative of the Soviets in Paris. Pyatakov, in his turn, often reported to Anastas Mikoyan, the Soviet minister for foreign trade. Some sources suggest that Stalin wanted Mikoyan to work directly with Gulbenkian as both were Armenians.

The director of the Hermitage, Boris Legran, didn’t dare to convey his concerns to the Soviet leadership about selling the masterpieces. But his deputy, Joseph (Hovsep) Orbeli, a Soviet-Armenian historian and orientalist, did. In 1932, Orbeli sent a letter to Stalin asking not to sell the ancient Persian artifacts. The Persian pieces most probably would be sold to Gulbenkian as well. On October 25, Orbeli received Stalin’s reply: the Foreign Trade Department was instructed not to sell ancient oriental artifacts of the museum anymore.

March 18, 2022, marked the 135th anniversary of Orbeli’s birth. Not coincidentally, an exhibition on Persia was launched at the Hermitage. As was mentioned in one of Russia’s mainstream publications, if not for Orbeli, the Persian exhibit of the 21st century might not take place, implying that the Armenian academician saved the treasures of the ancient Orient from being sold. The records suggest that Orbeli not only saved Oriental artifacts. After having Stalin’s approval, the Hermitage’s curators decided to recatalog European valuables as Oriental artifacts to safeguard them from possible sales.

In 1934, Stalin made Orbeli the director of the Hermitage. During World War II, when the Nazis besieged the city of Leningrad and were bombing the museum, he stayed in the town and played a crucial role in saving the masterpieces of the Hermitage. In 1945, during the trial of the Nazi criminals in Nuremberg, Orbeli testified about Nazi attacks against his museum. When the lawyer of the Nazis asked, “Does he think the Luftwaffe hit Hermitage purposefully or by accident?” Orbeli answered, “I am not a military expert, but I can suggest the following: 30 Nazi bombs hit the Hermitage during the war, and only 1 hit the bridge in our vicinity.”

Between 1943 and 1947, Hovsep Orbeli also served as the first president of Soviet Armenia’s Academy of Sciences.

It is controversial, but it is a fact: Calouste Gulbenkian, one of the main buyers of the treasures from the Hermitage, also tried to prevent the sales of the masterpieces by the Soviets. On July 18, 1930, Gulbenkian wrote to Pyatakov: “You might ask, why am doing this, considering that I am the one who is trying to buy the artifacts. Perhaps you remember that I have always recommended and continue suggesting now that your government should not sell museum artifacts.” Per Gulbenkian, the museum’s artefacts carry great educational importance and serve as a source of great national pride. “If word of their sale were to get out, it would harm your government’s credit,” he suggested.

After his death, the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum was set up in Lisbon, Portugal, where the collection was opened for public display. However, Dr. Conlin noted that initially, the Armenian art collector considered three other major locations: Washington, D.C., New York, and London. In Washington, a building between the National Gallery of Art and the Capitol Building was planned, and, per Dr. Conlin, a basic sketch of this venue was made. Evidently, the negotiations with New York’s Metropolitan Museum and London’s Museum advanced a bit further. Dr. Conlin found a 1940s photograph of the proposed “Gulbenkian Annex” model at the National Gallery, London, which would have stood to the west of the main building on London’s Trafalgar Square, which is the heart of the city.

The parties disagreed on the design of the display. Gulbenkian wanted all his artifacts to be exhibited at one location. Contrary to that, the museum authorities insisted that each piece should be placed next to other related artifacts. As a result, none of those projects came into existence, and the Gulbenkian treasures ended up and continue to be displayed in Lisbon.

Andrew Mellon pursued a similar goal. He wanted Washington to have a gallery of art like the English gallery established in the 19th century. With that vision, he purchased about 20 paintings from the Soviet government, paying about $120 million in today’s nominations. The construction of the gallery started on the National Mall in 1937. Melon’s endeavor was again not without Armenian engagement.

I visited the Keshishian rug store in Rockville, Maryland to learn more about this project. Mark Keshishian, the current owner, told me and showed evidence that before moving to Maryland, the Keshishian rug dealers ran their store in Washington, D.C., not far from where Andrew Mellon lived. James Keshishian, the father of Mark and one the earlier owners of the family business, left memoirs that Mark showed me. James noted that in the 1930s, the US government rented the two stories of the Keshishian rug store. “There were three federal officers on duty at the elevator and the stair doors next to the elevator. The two sat facing each other at the doors on the second and third floor,” recorded Jim Keshishian in the family history book.

The US federal officers carried pistols and Thompson submachine guns. “They would take the bullet holding drum off to clean them, and they’d let me hold them. They were very heavy,” wrote Jim Keshishian in the family history account. But what were the federal officers protecting at the Armenian-American store?

“There were a lot of framed paintings deposited against the walls on the two floors. They were stacked four, five, and six deep against each other. People would rearrange them from time to time,” wrote Keshishian in his memoirs. As he would find out later, the Mellons kept the masterpieces on the two stories of the Keshishian rug store building.

The Mellons themselves lived close by, on two stores of the six-story building on what is now known as McCormick Apartments, aka the Andrew Mellon building, on 1785 Massachusetts Avenue. Another resident of that same building was art dealer Joseph Duveen. In 1936, a year before his death, Mellon paid 21 million dollars to Duveen to obtain his paintings and sculptures. Per National Geographic Traveler, at the time, this was the biggest transaction on record. Most probably, it was after this purchase that Mellons decided to rent the two stories of the Armenian rug store. Jim Keshishian believes the Mellons rented part of their rug store in 1936.

Paul Mellon, the son of Andrew Mellon, knew Mark Keshishian the senior, the store owner at that time, personally. The Keshishians also lived nearby on Church Street, and the Keshishian store serviced the Mellon family’s rugs at home.

Andrew Mellon did not live long enough to see the opening of the National Gallery of Art. It opened on March 17, 1941, in the presence of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Paul Mellon. As noted earlier, the Gulbenkian museum could have been adjacent to it.

The Armenian presence in such a significant project as the sales of artifacts from the Hermitage and the foundation of the National Gallery of Art on the National Mall is a fascinating story to be recorded and further researched.

The Armenian Mirror-Spectator