FRESNO — Dr. Taner Akçam shared new revelations about the planning of the Armenian Genocide during a lecture at Fresno State University on March 3. Akçam, director of the Armenian Genocide Research Program at the Promise Armenian Institute at UCLA, has discovered new telegrams and validated previously known documents sent by members of the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP, or “Ittihad” – in Turkish, Ittihad ve Terakki Cemiyeti) political party during the First World War which shed new light on how and when the decision was taken to implement a full-scale annihilation of the Ottoman Armenian population.

Conflicting Theories on Intent

Akçam related how some of the leading scholars of the Armenian Genocide have disagreed on the extent to which the Genocide was premeditated. Vahakn Dadrian, known as the father of Armenian Genocide scholarship, and Akçam’s mentor, believed that there was always a long-range goal to eliminate the Armenian people, and the First World War merely gave its perpetrators, CUP, the political party that ran the Ottoman Empire as an authoritarian one-party state from 1913-1918, the pretext and cover to enact their plans.

Other scholars, such as Ronald Suny and Donald Bloxham, have opposed this thesis, arguing that the decision to eliminate the Armenians was taken during the war in connection with the Russian defeat of the Ottoman military at the battle of Sarikamish on the Caucasus Front (January 1915), and the British and Allied assault on Gallipoli (March 1915), beginning a campaign which threatened to capture Constantinople. These scholars have argued that as the Ottomans began to see the Armenian population as an internal threat in a war that they were starting to lose, they resorted to drastic measures.

Akçam stated that both schools of thought were ultimately based on speculation, as there was not enough evidence at the time to really understand the development of the CUP’s “Final Solution.” While the evidence clearly pointed to genocidal intent and state-sponsored extermination, when and how the plan was decided upon was unclear, and scholars would make suppositions based on circumstantial historical facts, (i.e. “Enver Pasha blamed the Armenians for the defeat at Sarikamish.”)

With newly discovered and/or verified telegrams from the Ottoman Archives, Akçam revealed new insights as to how the atrocities unfolded, which challenged some of the accepted historical assumptions.

Decision Was Made in Erzurum, Not Istanbul

Akçam stated that while the ultimate decision to eliminate all Armenians in Anatolia and Western Armenia was taken by the CUP’s Central Committee in Constantinople (led by the triumvirate of Mehmet Talat, Ismail Enver, and Ahmet Jemal), he displayed new evidence showing that the “first decision” to annihilate Armenians was taken in Erzurum on December 1, 1914.

It was the Central Committee of the Teshkilat-i Mahsusa (“Special Organization,” the corps of ex-convicts and Kurdish tribesmen who were answerable directly to the CUP leaders), headquartered in Erzurum, which on that date gave the order to their forces that “those suspected of being potential leaders of the revolt or liable to carry out attacks against Muslims should be arrested and eliminated.”

While on the surface this is an order to arrest and execute suspected revolutionaries, it was quite easy to construe “potential leaders of the revolt” as “all Armenian adult males.” Furthermore, as Akçam pointed out, the Nazi leadership of Germany used the exact same wording when ordering all Jewish men discovered beyond the front lines to be killed during “Operation Barbarossa” (the German invasion of the Soviet Union). Akçam notes that instead of killing just men, the German SS exterminated the entire Jewish population in the area.

Andonian Papers and Dr. Bahaeddin Shakir

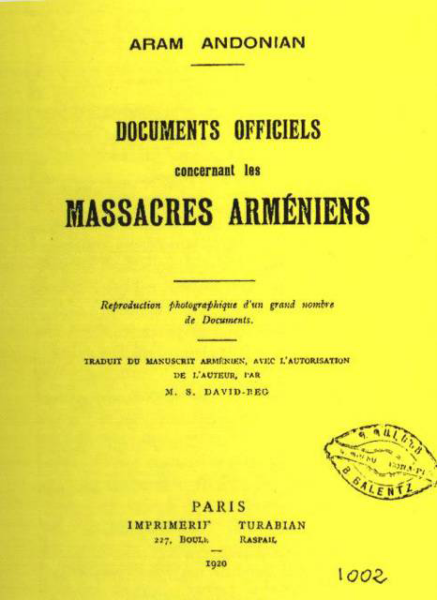

Akçam set the stage for his new research by overviewing some of his earlier discoveries in regard to the so-called “Andonian Papers,” which he published in his 2018 book, Killing Orders.

In 1921, Armenian writer Aram Andonian published a book in Paris called The Great Crime, which included telegrams given to him in Aleppo by Turkish official Naim Bey. The telegrams were purportedly sent from high-level Ottoman officials and included orders to wipe out the Armenians. The telegrams, written in Ottoman Turkish, were for decades claimed to be forgeries by Turkish denialists. The fact that these telegrams were the clearest proof of intentional state-sponsored genocide against the Armenians, made it very hard to write clearly about the history of the genocide in an “unbiased” manner when many scholars could not agree on whether the telegrams were genuine. Akçam’s research, published in Killing Orders, proved that the telegrams were indeed authentic.

One of the most important telegrams was written on March 3, 1915 and sent to the party secretary of the Adana branch of the CUP. The telegram reads, in part, “The Committee…has decided to annihilate all of Armenians living within Turkey, not to allow a single one to remain, and has given the government broad authority in this regard. On the question of how this killing and massacring will be carried out, the [central] government will give the necessary instructions to the provincial governors and army commanders.”

If this telegram is authentic, it would be the earliest evidence of an empire-wide plan to annihilate all Armenians. However, even though Akçam proved that most of the telegrams were authentic, this particular telegram was still in question as the signature at the bottom was too hard to read, though it seemed to say “Beha,” the meaning of which was unclear. But a 2017 book by a Turkish scholar from Ankara published the entirety of a CUP “notebook” still in a library in Istanbul, which included all the telegrams sent by Dr. Bahaeddin Shakir, head of the Teshkilat-i Mahsusa and widely considered one of the architects of the Armenian Genocide. Through this recent research, as well as research into Ottoman Turkish newspapers which Shakir wrote articles for, Akçam was able to verify that Shakir used the nickname “Beha” to sign many of his articles, and the signature at the bottom of the telegram was identical to that of Shakir, a fact that even Andonian was unaware of.

Shakir was in Erzurum in August 1914, returned to Istanbul in March 1915, and went back to Erzurum in April 1915, and thus Akçam deduced that the decision to commit the Genocide was taken by the Central Committee of the CUP, of which Shakir was a part, during the time he was in Istanbul, which coincides with the time that the telegram was sent. On March 14, another telegram was sent which stated “refer to Third Army Command in regard to the urgent measures to be taken in response to Armenian actions,” while an April 7 telegram stated, “the committee has decided to annihilate all Armenians living within Turkey.”

Based on these and many other telegrams, Akçam concluded that the final decision must have been taken between February 16 and March 3, 1915.

Tracing Clues Back to Erzurum

But why was this decision made at this particular time, when Shakir was in Istanbul? To answer this question, Akçam traced the history of the telegraph correspondence between Talat Pasha, the de facto dictator of Turkey during the war, and Shakir.

On November 26, 1914, Talat had sent a telegram to the government office in Erzurum, asking them to call for Shakir to come to the city of Erzurum and to the telegraph office so that he could communicate directly with the Central Committee. At the time, Shakir was in the region but not in the city of Erzurum.

On February 16, Shakir arrived in Erzurum and began to communicate with the party leaders in Istanbul; this was most likely when the final decision was being made, argued Akçam, but he pointed out that we don’t have a record of these communications.

However, Akçam’s research shows that earlier decisions had been made in Erzurum, even before Shakir arrived there. Although the final decision affected the whole Ottoman Empire, the decision taken in Erzurum on December 1, 1914 affected also the provinces of Mush and Van, or in Akçam’s words “half of Historical Armenia.”

Akçam mentioned that once again, there are not many documents related to the December 1 decision, but “it’s not just because the Turkish government or deniers take them away.” Akçam noted that during the original communications, the officials were often supposed to burn telegrams after reading them, so that although some survived, many telegrams are long gone. In another telegram to Talat, Shakir stated that he had to come to Istanbul “because I have some thoughts and opinions that cannot be put down on paper.” Akçam surmises that these related to increasingly drastic measures against the Armenian population.

Akçam discussed that during all of December 1914, the CUP Committee in Erzurum as well as Tahsin Bey, the Governor of Erzurum Province, sent telegrams to Istanbul, making a list of the decisions they made. One telegram read that “those Armenians, both in the city centers [Bitlis and Van], and in surrounding villages who are suspected of being potential leaders of the revolt or who would attack Muslims are to be arrested in advance and in case of attacks on Muslims they [those arrested] are all to be deported to Bitlis immediately in order that they be exterminated.”

Akçam noted the importance of the wording of this document. The orders were to target Armenians “in advance” of their “potential” revolt. This was long before the Defense of Van in April 1915, which many Turkish denialists use as a proof of Armenian rebellion which was met with retaliation by the state. Instead of responding to actual Armenian rebellions, Akçam argues, the CUP began to view Armenians as “potential” revolutionaries and traitors to the Empire. Thus, any Armenian could be suspect as an “enemy of the state.”

Radicalization Came From the Provinces

Akçam made a compelling argument that not only was the first decision on the Armenian Genocide made in Erzurum, rather than Istanbul, but that the increasing radicalization of the Armenian-Turkish issue and the push for genocidal measures was less of a top-down phenomenon as and more the result of the demands by provincial governors.

In a telegram dated December 20, 1914, Tahsin Bey, the Governor of Erzurum, proposed to the central government that “the previous decision taken by the Erzurum central committee … be immediately put into effect in other provinces too.”

Akçam’s argument is that the local governors were pressuring the central government in Istanbul to make a centralized decision to exterminate the Armenians in all provinces. As Akçam put it, this new information alters our current understanding of how and why the Genocide took place. The traditional view was that the atrocities were primarily planned and executed by the CUP triumvirate and their fellow party leaders, in Istanbul. Thanks to Akçam’s new research, we now know that governors played a more important role than we realized. They were not merely passive receivers of orders from Talat and Enver.

One important discovery, said Akçam, is that the governors communicated with each other and made decisions in the regions. It is significant that they were the ones who kept pushing the idea that the Armenians really need to be exterminated.

Even before the Erzurum Central Committee had made their decisions, Governor Tahsin was sending telegrams to Istanbul suggesting the same. For example, on November 17, he wrote “The time has come to take a permanent decision and issue an order in regard to the Armenians.” Meanwhile, the authorities in Istanbul replied that Tahsin should carry out whatever the situation demands “but with well-considered measures until a decisive order is given.” Akçam summarized this as “the governor is pushing, but Istanbul is staying calm.”

Another governor, Jevdet Bey of Van, wrote on November 19 that to “intentionally wait until the blaze gets of the control would be disastrous for us,” and “we stand before another disaster like what was experienced in Rumelia,” when the Ottomans lost territory to the newly-minted Balkan states. He suggested that “without waiting for the Armenian rebellion,” the Turkish authorities should act “as forcefully as possible.”

Akçam again pointed out that mirroring the Holocaust, the paranoia of the CUP led them to genocide, as their logic was “whoever seems suspicious” of disloyalty to the state could be a “potential threat,” and therefore “should be eradicated.” That essentially means that “all Armenians should be eradicated.”

If it took until December 1 for the CUP leadership in Erzurum to decide upon eliminating the Armenians in the Eastern Provinces, and until March for the leadership in Istanbul to follow suit for the whole Empire, telegrams had been pouring in from local governors before that time. Throughout November and December of 1914, the governors of Erzurum, Van, and Bitlis, were demanding a final decision on the Armenians and for the government to give them permission to use radical measures, but no decision was forthcoming until March.

Conclusions

Before making his final conclusions, Akçam noted the importance of the fact that in all of these secret telegrams, the word “extermination” is used, while most Turkish denialists have for years denied that there was any intent to “exterminate.” Some other synonyms used in the telegrams were “persecution and elimination,” or “annihilation and elimination.” In April, telegrams spoke of “the annihilation of Armenians to the greatest extent possible, together with their material and moral power,” a clear reference to genocide.

The early decisions for extermination are significant for having been made in the period before either the British Gallipoli landing and the Ottoman defeat at Sarikamish, both of which have normally been posited as incitements leading to the genocide.

Akçam had been scheduled to also discuss new research on the role of the Kurds in the Armenian Genocide, but did not have time. Upon the request of the audience, he shared some tidbits of local provincial governors, including the aforementioned Tahsin, Governor of Erzurum, who in their telegrams complained of Kurdish tribes attacking and looting Christian, including Armenian, villages, and requesting more security forces to fight these Kurds. Why would Turkish officials who were simultaneously suggesting that the entire Armenian population be wiped out, ask for help to essentially stop Kurdish tribes from wiping out the Armenians? Akçam left this tantalizing question for the audience to ponder in expectation of his next lecture, when, he said, he would share his hypothesis.

The Armenian Mirror-Spectator